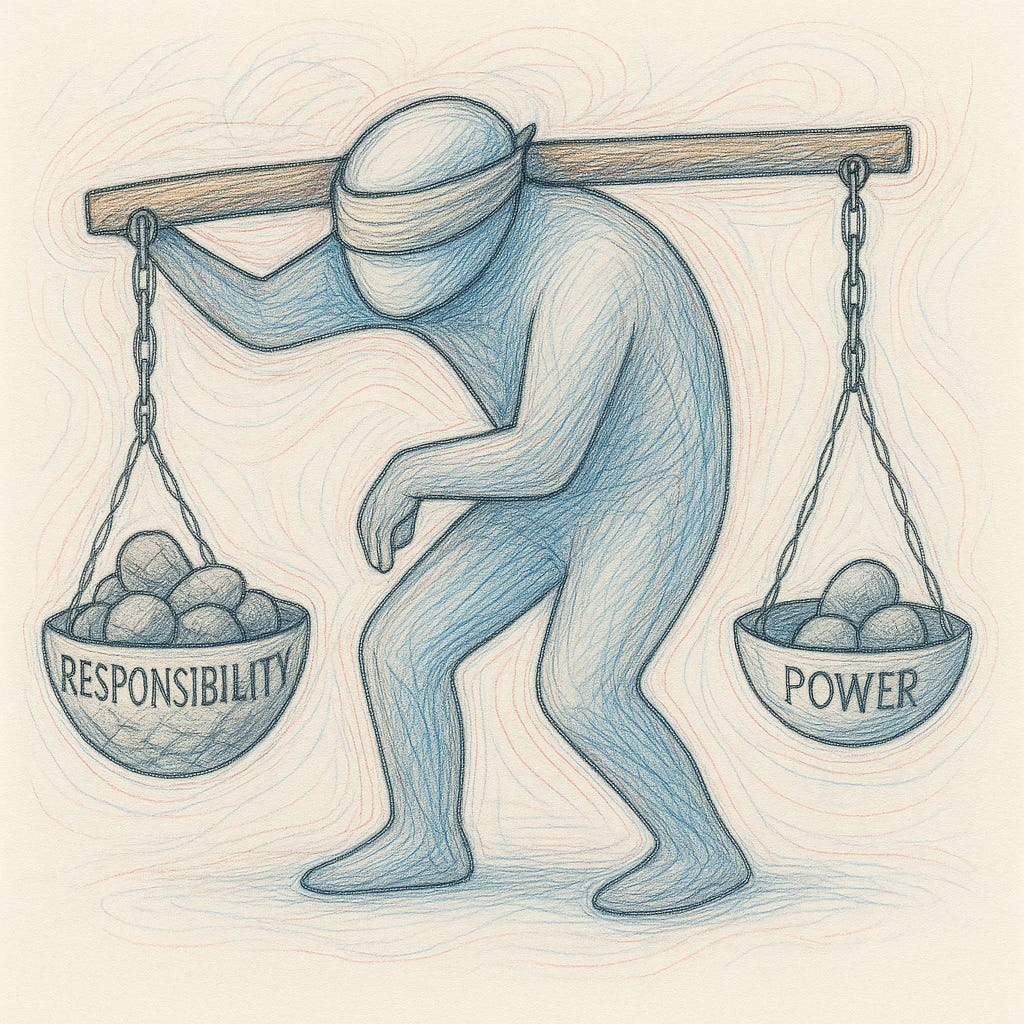

The Crushing Weight of Power Blindness

How Our Over-Responsibility Is Doing More Harm Than Good

In my last post, I argued that the primary cause of so much of our distress, depletion, and dysfunction is what I call over-responsibility—the quiet but unyielding habit of carrying burdens that aren’t actually ours to bear and are, by nature, impossible to fulfill.

I saw it in my clients, my coworkers, and the people I love—spinning their wheels trying to fix what they couldn’t control. And I saw it in myself.

So how do we let go of this excessive responsibility? The answer seems simple: figure out what you’ve taken on that isn’t yours, and put it down. But in practice, it’s not that easy.

Why? I’m still exploring that question. But for starters, the unconscious and often deeply entangled forces that encouraged us to pick it up in the first place make it incredibly hard (if not scary) to let it go. That’s because our sense of responsibility isn’t something we typically arrive at through conscious discernment. It’s something that’s been shaped reactively—formed by culture, relationships, survival strategies, and lived experience.

And even when we try to discern what we truly ought to carry, we’re often working from a definition of responsibility that’s unclear, if not fundamentally flawed. Maybe even backwards.

To understand why this is so hard to shake, we first need to understand why it’s so hard to see. And then we can start to uncover how our confused assumptions about responsibility might be what’s keeping us stuck.

Over-Responsibility Is Both Unrecognized and Unrecognizable

Part of what makes over-responsibility so elusive is what we’ve been taught—both explicitly and implicitly: that responsibility is always a virtue.

I hear this all the time in response to my writing: “But I thought responsibility was a good thing.”

Of course it makes sense. Culturally, we admire responsibility. We praise it in kids, reward it in adults, and equate it with strength, character, and maturity.

And our language reflects that. We have plenty of words for too little responsibility—irresponsibility, negligence, avoidance—but almost none for too much. We don’t have a shared vocabulary for the choice to carry more than we can, or should.

Which raises a deeper question: Do we even believe it’s possible to be too responsible? And if we do, how are we supposed to know—with any clarity—what’s right and what’s too much?

Most of us were never given a clear framework for recognizing the bounds of healthy responsibility. We often don’t go looking for one until we’re already feeling the consequences—whether through personal strain or the feedback we get after we’ve overstepped.

Without that clarity, our understanding is shaped by something else: the environments that formed us.

It’s shaped by cultural messages that loudly promote altruism while quietly whispering ‘eat or be eaten.’

It’s shaped by the modeling of parents, teachers, and leaders who blurred the lines between care and control, or between service and self-neglect.

It’s shaped by relational, communal, and societal dynamics where responsibility was distributed inappropriately: impulsively, unjustly, or manipulatively.

And for those who were abused, neglected, or simply expected to hold things together too early, over-functioning often became a strategy for survival.

Over time, these patterns don’t just influence us. They become us.

What began as a coping mechanism—carrying more to feel safe, connected, or in control—slowly becomes second nature. And eventually, though we still feel powerless, we become the ones holding the most power—shaping the people and systems around us.

We rarely question these instincts because they look good on the surface. They get praised. They feel familiar. We call it being smart, tough, responsible, or mature. But what we often call “maturity” isn’t rooted in discernment. It’s rooted in anxiety, obligation, and the quiet fear that if we stop holding it all together, everything will fall apart.

We say we’re doing what’s right. But more often, we’re doing what feels necessary—to preserve our sense of safety and maintain some illusion of control.

Here’s the kicker. Our definition of “responsible” is often based on the wrong criteria. And that confusion may be exactly what’s keeping us stuck.

To highlight just how deeply the confusion runs, let me reflect briefly on my history of wrestling with a school of philosophy that always left me uneasy.

We’re Asking the Wrong Questions About What’s Right

You’d think that a desire to do good and live with integrity would naturally draw me toward ethics. And in many ways, it did. But my experience with ethics—both philosophically and practically—has been... complicated.

In school, traditional ethics often felt too abstract to be useful. We spent hours debating hypothetical dilemmas while the world burned around us. In my professional life—particularly in the mental health field—ethics often centered on risk management: codes meant to prevent harm and limit liability, but with little grounding in the deeper realities those rules were meant to address. As a newer counselor, I often felt anxious about making the wrong call, especially when the situations I faced didn’t fit the case examples we’d been given.

So when I was later asked to teach our program’s ethics course, my first reaction was an honest, reluctant: “Ugh...” But over time, I began to understand why. The frameworks I’d been handed felt disconnected from reality—especially the reality I needed to navigate wisely and well. And eventually, it led me to a larger realization:

Most ethical frameworks begin in the wrong place.

They begin with ideals and outcomes—abstract principles, desired results, or prerequisite character traits. But those are all downstream concerns.

What gets missed is the source:

What kind of power do we actually have—and how are we designed to use it?

That’s where the conversation must begin—because the very reason we need ethics in the first place is power. Power is what makes both harm and good possible. It’s what makes us culpable. And that’s why it’s the basis of all responsibility.

Starting with ideals and outcomes is like dreaming up a beautiful meal without first checking what ingredients we actually have—or whether they’re even attainable. It might sound inspiring, but it’s untethered from reality. And that makes it a recipe for failure.

Misused Power Always Misshapes the Self

When our ideals and outcomes blindly outpace our power, the consequences aren’t just disappointing—they’re deeply damaging, not only to others, but to ourselves. That’s because, as agents, we are always exercising our agency. We don’t just have and apply power—we are power in motion. Every act of agency is also an act of self-application. So when we misuse our power, we simultaneously misuse—and misapply—ourselves.

This brings me to a second major realization:

If we want to discern what is good, we can’t stop at simply evaluating the power we hold or how it functions to produce the outcomes we want. We must turn our attention inward—examining who we are and how we’re designed to work and thrive. That includes becoming intimately familiar with our dynamic, interdependent, and even nurturing relationship with power itself.

Too often, we approach both power—and ourselves as agents—as if we’re tools: instruments for achieving outcomes, valued primarily for what we can produce. But power isn’t merely a tool. It’s a generative force—something to be cultivated, tended, and stewarded over time. When we ignore power’s design, we risk becoming disconnected from the very source that sustains our ability to do good—and become good—in the process. We don’t just squander our power; we squander ourselves.

A truer way to understand both power and agency is through the lens of cultivation. We are like gardeners, entrusted to nurture the conditions that make growth possible: investing and growing, reaping and resting. And we are also like plants, wholly dependent on those same conditions—not just to bear good fruit for others, but to root deeply, grow fully, and flourish in the process.

What Most Frameworks Miss—and Why We Stay Stuck

This fundamental reality—the nature of our power—is often overlooked, assumed without question, or treated as an afterthought in many ethical frameworks. And those frameworks, in turn, reflect the everyday assumptions we carry about responsibility. By centering on ideals and outcomes, they often bypass the prerequisite conditions for doing good—and the design that makes it sustainable.

Ideals and outcomes still matter. They reveal what we value and help us evaluate the impact we’re having. But they cannot define responsibility on their own. Unless our sense of responsibility is grounded in the power we’ve actually been entrusted with—and in the way we’re designed to wield it—we’re just guessing. And too often, we guess in ways that deepen our blindness, confusion, and harm.

Which brings me to the deeper problem: most of us don’t recognize our own power—if we recognize power at all. We don’t know what we carry, what it’s for, or how to tell when we’re misusing or neglecting it. We operate without a clear internal compass for aligned responsibility—because we’ve never been taught to notice our agency, much less understand how it’s designed to work.

Until We Understand Power, We Will Struggle to Do (and Feel) Good

When we aren’t conscious of our power—what we actually have and how we can or cannot use it—we start assuming responsibility based on all the wrong cues. We respond to urgency, pressure, expectation, and moral weight, whether or not something is truly ours to carry.

Without clarity, we default to external demands and visible outcomes. We feel compelled to over-function, overreach, and overextend—because stopping feels risky, or even wrong. When our efforts fall short, we panic, shut down, or numb ourselves against the grief of powerlessness. And just as we begin to burn out, another demand or opportunity arises—sparking hope, or guilt—and the cycle begins again.

Over time, this misalignment wears us down—and shrinks both us and our lives. We stretch ourselves thin trying to fix what we can’t control, while overlooking the quieter places where our power actually lives—especially the responsibility to care for and invest in ourselves. What we can influence often feels too uncertain, too slow, or too small to matter. So we become reactive, brittle, and burdened: strangely responsible, yet disconnected from any real sense of agency.

No wonder we get stuck. When we can’t locate our power, we can’t steward it. And when we can’t steward it, we lose the ability to do good and live wisely—to feel good and alive.

If we want to change this, the way forward begins with honest attention. We must start observing how power actually operates in the daily details of our lives—especially in the places where we feel powerless—so we can begin to reclaim and exercise it differently. So we can feel more grounded, present, and free.

And if we want to do it well, we’ll need to do it together.

Power is hard to see on our own. We need shared language, honest reflection, and spaces where we can compare notes and ask better questions. Together, we can learn to recognize our patterns, recover our agency, and rebuild our sense of responsibility on more honest ground.

Recovering from over-responsibility—and beginning to live with more clarity, intention, and power—takes time. But it’s possible. And it’s lighter when it’s shared.

I’m committed to continuing this conversation and walking alongside others who are choosing a different way: one that’s more sustainable, more energizing, and more deeply human.

If that’s the path you’re on, I hope you’ll pull up a chair and join the conversation.

You’ll be in the company of some of the best people I know—most likely because you’re one of them.

Is Everything Over-Responsibility and Power Blindness?

Maybe. And that’s the point.

(If that question came up for you, read on…)

Last night, my family stumbled across an interview with John Green, the author of a new book called Everything Is Tuberculosis. The title sounded absurd—until he explained how the disease quietly shaped everything from city planning and hospital design to public health policy and beauty standards. Its influence was massive. And its invisibility made it even more so.

That kind of quiet, systemic influence? That’s exactly how over-responsibility and power blindness operate. They don’t just burden us individually—they rewire us collectively. They’re self-reinforcing personal patterns nested inside self-reinforcing cultural ones. Subtly and persistently, they shape what we believe is ours to carry and how we measure ourselves for carrying it. Like the air we breathe, they surround us—unseen, yet suffocating. And the more invisible they are, the more powerfully they operate.

You can see the hunger for relief everywhere. Let Them by Mel Robbins is a bestseller because people are desperate to put down what was never theirs. Therapeutic models like Internal Family Systems are gaining traction because they help us recognize—and release—the over-functioning roles we were never meant to bear. And Jesus’ ancient invitation still holds sway because it speaks to our present soul-fatigue and heaviness: You don’t have to carry that anymore.

Over-responsibility and power blindness may not be the only problem. But they’re the thread beneath so many others. They reveal our disconnection—and invite us back into alignment. Not by becoming more, but by becoming more fully ourselves.

That’s the work. That’s the way forward. It starts by asking who you’re meant to be—again, or for the first time.

And beginning right where you are, one honest step at a time.

Reflection:

Where in your life are you carrying responsibility that isn’t really yours?

How is it showing up—in your body, your thoughts, your relationships?

What is it costing you?

If you started to set it down—even just a little—what might shift?

What might you begin to feel?

Who might you get to be?

What’s one next step you could take to loosen your grip on what isn’t yours—and reconnect with what is?

I love this framing so much! In the process of becoming a mother 6 years ago I felt like I could ‘see’ my power for the first time — its realness and its limits.