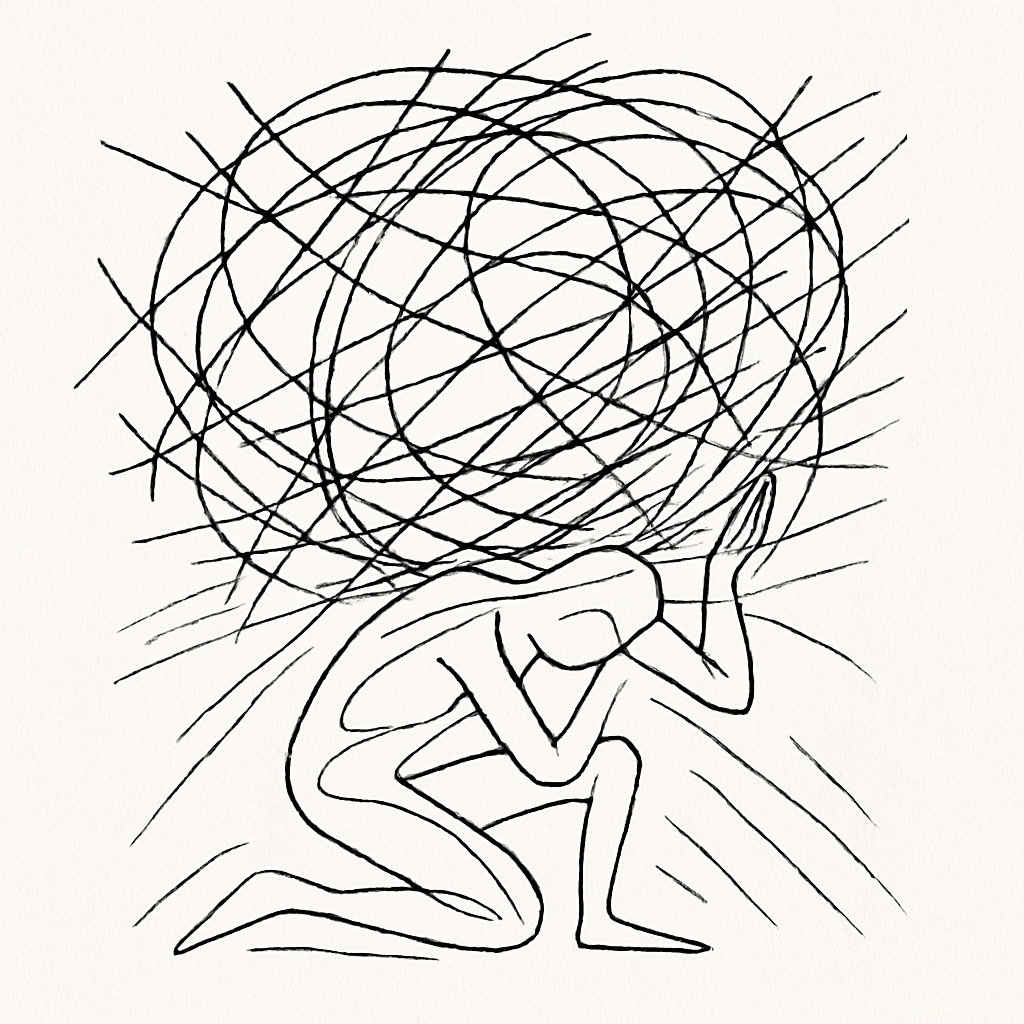

You Are So Tired (and Still Can’t Stop)

Why caring and carrying too much is quietly costing us everything

We care deeply, we try relentlessly—and still, it never feels like enough. It’s time we start talking about why.

This morning, after the kids caught the bus, I noticed it again—the slightly crumpled Mother’s Day card my son had made at school. He knows I love gardening, so he’d drawn a watering can overflowing with flowers, vegetables poking out at odd angles. Scrawled in fourth-grade handwriting across the can: “Best Mom Ever.”

But I didn’t feel like the best mom. Not even close.

The night before had been rough, with too many reminders to get back in bed. The morning was worse: constant prompts to get dressed, rising tension with my husband, and last-minute scrambling to pack lunches and get out the door. I was barking orders from the other room—impatient, frazzled, and increasingly frustrated. And when someone spilled chocolate milk on the new rug in their bedroom (where food isn’t even allowed), I snapped.

When the house was finally quiet, I felt hollow. Disappointed not just in how I’d treated my family, but in how I’d treated myself.

As I retraced my steps, I could see the progression. I’d been brushing off my daily check-in routine, the practice I depend on to pause, ground myself, regain perspective, and move forward with intention. I’d missed the signs of creeping overwhelm and exhaustion. I’d slipped back into firefighter mode: reacting to unspoken pressure, pushing through instead of pacing myself, treating myself less like a person with limits and more like a machine built for outcomes. And when even that wasn’t enough, I started treating the people I love the same way. I felt trapped in an impossible situation, wondering why no one was stepping in to help.

My outburst over spilled milk wasn’t just a bad parenting moment. It was a cry for rescue—because I genuinely believed I was drowning.

With some distance, I can see the fuller picture. I wasn’t the only one who misstepped, and given the context, compassion is warranted. I’m parenting neurodivergent kids, supporting a spouse through cancer treatment, and running a business in a season where just surviving feels like a full-time job. Even now, I’m not entirely sure what I could’ve done differently to shift how things unfolded.

But I am clear on one thing. My spiraling wasn’t primarily a result of difficult circumstances.

It was a consequence of my sense of responsibility. Or rather, my disordered sense of responsibility.

My certainty of this comes from decades of studying it in myself and others like me—and realizing it’s actually a thing. A way of operating that’s surprisingly common and rarely named—often mistaken for altruism, maturity, or strength—but far from benign.

It’s behind so much of our exhaustion, frustration, and quiet pain. And over time, it costs us—and the people we care about—the very things we most need to thrive.

Let me try to explain…

The Try Harder Disease

Early in my counseling career, I expected to work with people who were struggling to function. But most of my clients had the opposite problem: they were struggling with over-functioning.

They were people who cared deeply and carried a lot of responsibility. Attentive, conscientious, empathetic, and hardworking, they often held leadership or caretaking roles—at work, in their communities, and in their families. By all accounts, they were ideal clients: motivated, thoughtful, self-aware, and invested in doing good. Honestly, some of the best people I’ve ever known.

But over time, a pattern emerged. After weeks, even months, of exploring issues, trying strategies, gaining insight, and shifting behavior, we’d find ourselves stuck. Despite all their effort, we seemed no further than where we had started.

Why? Because the problems they were trying to solve weren’t primarily the result of their own choices. And while they were deeply distressed or personally impacted by the fallout, they lacked the capacity to truly change the outcomes.

At that point, I would usually offer a compassionate invitation: to stop holding themselves responsible for what they couldn’t control.

Their response almost always sounded something like: “Yeah, I just need to remember that… pray more… stop caring so much…”

Even putting down responsibility became another form of striving. And before long, they’d be back to analyzing and troubleshooting, hoping this time would be different.

They couldn’t let go. The more helpless they felt, the more determined they became, and the harder they tried to dig themselves out, the deeper they sank.

From the outside, it looked noble. And to them, stopping—not trying—felt selfish and wrong, like a betrayal of their values, their people, even themselves.

But underneath, it mirrored compulsion, functioning more like an addiction than a virtue. The very thing they clung to for survival was quietly draining their health, their hope, and their humanity.

As this pattern emerged in my clients, something else became clear: I couldn’t lead them to another path—because I was just as stuck as they were.

That’s because we shared the same default strategy for life. Which meant that, despite my compassion and desire to help, I had no unique solution to offer. I’d learned how to minimize or manage the dysfunction in my own story, but in that office, I couldn’t look away. Because I was looking at myself.

And I knew I couldn’t offer real help—something I cared a great deal about—unless I figured out what could free us from this self-imposed prison.

In the years that followed, I set out to understand this relentless “try harder” disease, sometimes out of curiosity, more often out of sheer desperation. What was driving it? Why was it so hard to identify and name? And what might finally open a path to recovery—not just for the best people I knew, but for me too.

Here’s a snapshot of what I’ve found so far.

The Many Faces of Over-Responsibility

For lack of another available term (something worth noting…), I’ve come to call this dynamic over-responsibility.

Over-responsibility is at play anytime we assume responsibility we can’t actually fulfill—either because it falls outside our rightful domain or exceeds our capabilities. Fundamentally, it’s misplaced or disordered responsibility that shows up in both our thoughts and behaviors.

It manifests in how we function in relationships—with individuals, families, teams, organizations, and communities. But it also shows up in how we engage with our work, environment, possessions, bodies, decisions, thoughts and emotions, actions and beliefs, and even our connection to the spiritual realm. In short, any part of life can become a place where our sense of responsibility quietly stretches beyond what we can—or should—carry.

You’ll often find it at the root of our:

People-pleasing, social temperature-taking, over-apologizing, over-giving, over-compensating

Perfectionism, workaholism, ruminating, over-analyzing, over-explaining, over-predicting

Protecting, scrutinizing, manipulating, arguing, blame-shifting

Peacekeeping, minimizing, numbing, escaping

We usually think of these behaviors—people-pleasing, over-analyzing, perfectionism—as personality quirks or coping mechanisms. But more often than not, they’re symptoms of the same underlying belief:

If I want something, be it security, connection, significance, or safety, it’s up to me to make it happen.

That’s how we get pulled into a relentless “try harder” loop: a self-reinforcing cycle where responsibility is assumed automatically, without ever asking whether it’s ours to carry. Failure tells us we didn’t try hard enough. Success tells us we’re doing it right. So we double down. Try harder. Give more. Do better. Don’t stop.

But the loop is unsustainable. The work never ends, the results don’t last, and the goalposts keep moving. And because it feels necessary—even morally unquestionable—we rarely recognize it for what it is: a game we can never win, one that slowly makes us wonder if we’re just losers—but one we’re increasingly afraid to quit.

What It’ll Take to Stop

If we want to break free from this addiction, we have to understand how we got here—and why.

We need to examine what’s been quietly informing and driving our over-responsibility so we can address it at the root. And we need to clarify what actually determines the bounds of our responsibility—so we can know what’s truly ours to carry, and how to thrive while we carry it. The answer might surprise you.

Thank you, Laura, for this post on the "try harder" disease: "we need to clarify what actually determines the bounds of our responsibility—so we can know what’s truly ours to carry, and how to thrive while we carry it." I'm looking forward to reading Part 2 in your series.

I feel I have a disordered sense of responsibility too, I definitely see myself in the everyday moments you captured.